My friend Euni gave me The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint Exupery, one of her favourites. I'm not really sure how to describe it. The prose is simplistic, like a children's novel, the narrative is fantastic and full of wonder as in a fairytale or fable, but the meaning, while certainly not buried deep, really ought to mean more to adults than children.

The Little Prince tells the story of a boy from a planet so small he can walk across it in steps, and uses his broom to clean out his (dormant) volcanoes. He travels across the solar system and lands on earth, where he runs into a stranded pilot in the desert.

It's such a slim volume that to say anymore would be to reveal most of the narrative, but suffice it to say that it's principle charm is to present things from the wonderful, expansive and creative viewpoint of a child, unemcumbered by the compartmentalization of adult life.

It recalls a conversation I had with the young daughter of a woman I once worked with at a pharmacy. I forget, unfortunately, the little one's name.

She: Look at what I drew! Me: What did you draw? She: A cow. (proudly shows me a blank piece of paper) Me: Um, that's...um, where is the cow? She: It's eating grass, right there! Me: It's not there... She: It ate so much grass it exploded! (grinning)

***

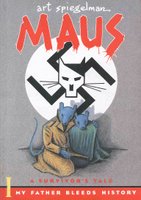

Maus, by Art Spiegelman is the account of one man's survival through the Holocaust. Spiegelman won a Pulitzer Prize for it, and with merit - it is unique on many levels. It is a graphic novel, for one (that's a fat comic book, for any non-believers). Spiegelman cleverly renders the Jews as mice and the Germans as cats, which serves three-fold: it takes the edge off a somber tale without sacrificing sincerity, it ties neatly into a propaganda statement the Nazi regime issued against Walt Disney and Mickey Mouse (a symbol of America and democracy), and it also allows the writer to, in moments of heavier introspection, to break the fourth wall by presenting himself as a human wearing a mouse-mask. Spiegelman, naturally, has the Jewish speech patterns and neuroses embedded deep, and the voices ring out.

Above all though, it's the very personal and unfiltered story of the survivor (Vladek), and how this affected his relationships with his son (Art), his wife (Anja) and his second wife (Mala).

Highly recommended. Anyone else out there got some good reading going?

No comments:

Post a Comment